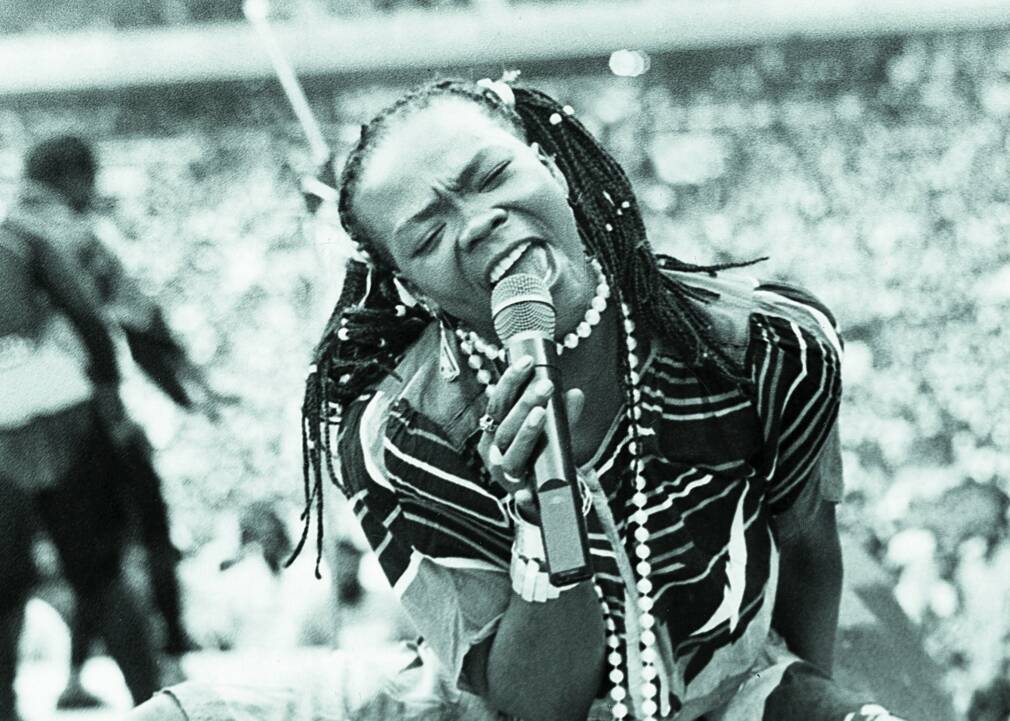

Most writings about Brenda Fassie start with an outrageous anecdote that pays homage to her unpredictable, super candid, strange and intense personality. In all of the different ways that we remember Fassie, her sense of humour, confrontational energy, gruelling tantrums, sweetness and rough, often tearful melodramatic edges all converge into this unforgettable ball of contradictions. Recalling his first encounter with Fassie in 1982, South African trumpeter Hugh Masekela sensed the audaciousness that we grew to both love and hate about her: “How the hell will she make it in the entertainment world with such a fucked up disposition?” With her crass disposition she went on to become one of the greatest musicians to ever grace South Africa. Fassie’s success transcended music and her highly evocative stage presence. Her performance gave many young Black people a space for willful self-identification. People could reinvent themselves from the template that Fassie presented – this wondrous image of a free, bad black girl, showing those alike in a time of structural and epistemic censorship and subjugation that they could be anything outside the prescribed parameters of existence for Black people. Reflecting on the confident legacy that Fassie inscribed, Bongani Madondo writes “with her animated energy, African braided, knee-length shiny plastic boots, sequins galore, the whip-cracking township punk-rock air swirling about her, she gave me and thousands of other black youths an opportunity to see ourselves as we so desired. We weren’t our parents. We weren’t obedient blacks. Although it took a long time for it to dawn on us who we were it didn’t matter.”

Brenda Nokuzola Fassie was born in KwaLanga, a township in Cape Town, South Africa on the 3rd November 1964. She was born into a big working class musical family and the youngest of nine siblings. Her mother, Makokosie Fassie, a domestic worker known as a phenomenal pianist and her father, who died when she was two, was fondly known for being a great singer. Her brother Themba Fassie, tells a story of how their father would come back from work and jump at the piano calling different members of the family to come sing with him or sing from wherever they were in complete harmony. Fassie’s personal upbringing revolved around music and performance, named by her brothers after the American country singer Brenda Lee, by the age of five she was already performing with her mother’s children’s band, the Tiny Tots. At this tender age, she had already developed an ability to enthrall audiences, singing for tourist and church events. Fassie’s popularity in the community grew, catching the watchful eye of renowned South African playwright Gibson Kente from Soweto known as the “father of black theatre.” After being told about Fassie’s great 16 year old talent, another exemplary producer Hendrick Koloi Lebona came to Cape Town from Johannesburg to visit her family and eventually ask her mother if Fassie could relocate to Soweto, Johannesburg for a career in music under Lebona’s mentorship.

In 1983 Fassie became the lead vocalist of a band titled Brenda & The Big Dudes, responsible for the hit track “Weekend Special”, which became an anthem for the punk and pop black South African township communities. With the further release of other popular tracks such as “Life Is Going On” they became the sound of the eighties and one of the most popular bands at the time. This band went on to dominate with dance tracks like “Oh what a night”, influential releases like “Can’t stop this feeling” and “Let’s stick together” – these releases marked Fassie at the helm of a burgeoning pop renaissance in South Africa. In 1985 Fassie gave birth to her only child, Bongani Fassie with then lover and band member Dumisani Ngubeni. With her rise in fame and fortune, Fassie’s love life became the centre of public attention and scrutiny. To some extent she played into the hands of the media while scornful about her dislike for its presence in her life and constant fabrication. Her love for attention, adoration and constant praise meant that she developed a complicated relationship with public life – always devouring any opportunity for attention to the extent of calling the press on her way back from Paris to announce that she would be divorcing her then husband Nhlanhla Mbambo because he had refused to send her money. To some extent Fassie invited the carnage and chaos that the media bought – its unforgiving presence continued into the nineties, a decade that marked the beginning of her demise and struggle with drugs and alcohol addiction.

Fassie is a product of her own engineering, of the uncontrollable circumstances that marked her presence as a Black person under apartheid South Africa. Her iconic status came out of what she was able to create out of the wasteland of working class status and how she managed to undermine aesthetic demands that stood against her – Fassie did not fit the image of palatable beauty, often labelled as ugly and unsellable, she pushed against the public’s reading of her as deviant from commercial beauty standards by owning her image in such a way that made it difficult for people to use her looks against her. Fassie peaked towards the disintegration of the Apartheid system, in the context of mass resistance in South Africa with many artist attempting to find their feet in the unstable political climate of daily riots, protests, boycotts and action against Apartheid repression. She peaked at the height of Draconian law enforcement that limited social and cultural life. The publications control board, acting as one of the Apartheid state’s propaganda machinery, closely examined record albums, books and songs banning anything that sought to politicise masses or condemn the government. Fassie’s iconic status emerged with a cultural revolution in South Africa, introducing some of the country’s most radical music with Brenda Fassie at its helm. She led the fort of musicians who introduced into the pop scene revolutionary lyrics that spoke to the realities of being Black in South Africa. She did so in witty, indirect, coded ways of speaking that are often open secrets in the streets. Her iconic music partnership with lyrical master, arranger, composer, and former Harari percussionist, Chicco Twala positioned her as the most influential and apt voice to reflect the plight of Black people.

Fassie’s astute work ethic and talent is one important factor that stole the hearts of Black South Africa but her love for Black people, their liberation and humanity, her living amongst them and softness solidified her as a trusted and loyal member of the Black, often chaotic, family. With songs like “Too Late for Mama”, Fassie’s wailing voice could be heard tearing up the speakers of many Black households, she sang of the plight of black people and particular hardships affecting women and mothers at the time. Songs like “Black President” are the pride and joy of Black memory in South Africa. For the first time, someone had made an explicit ode to the silent sixties through a song which defied censorship. “Black President” named the trauma suffered by the resistance movement in South Africa in the early sixties as a result of the Sharpeville massacre and with the arrest and banishment of Nelson Mandela and other Rivonia trialists. In “Black President” Fassie took us back to a time when we had no voice, under the collective repression of the State, she bellows the most memorable simple lyrics in classic Fassie untamed aesthetics :

The year 1963

The people’s president

Was taken away by security men

All dressed in a uniform

The brutality, brutality

Oh no, my, my black president

As a cultural worker, Fassie understood her task and knew that she had reached a point in her career that gave her leverage against state sanctioned violence. Her popularity and mass support gave her the security she needed to make her music. The love that black people afforded her gave her protection against arrest for violating the so-called regulations against anti government rhetoric.

This loving protection often did not translate unconditionally into her personal life. Fassie was the first openly queer black woman, musician, and celebrity in South Africa – this was difficult for many to accept without trying to label her as deviant or completely erase the spectrum of her sexuality. She often remarked “girls love me!” but spoke in a way that showed that she did not particularly identify with the language of queerness and labels but saw herself as a lover of people irrespective of their gender or sexuality. Without romanticising her, Fassie lived her private life in a public way, some of the more toxic elements of her love life were not spared the privacy that normal people are afforded with their mistakes and human faultlines often hidden. Fassie lived all of it, both the joyful and tragic moments on front row pages of obscene news outlets. You could walk past her life hung on news polls in the city centre with bold headlines enough to cause any human psychological harm and a deep dislike, if not hatred for the media and its hangers-on. But it’s a bit more complicated with Fassie, she was also addicted to drama, attention, and child-like affirmation. She was known as someone who needed constant adoration, it’s often said that loving Brenda Fassie was a fulltime job. She often tripped on her own ego, inner child longings that cannot be fully pathologized by unfair headlines. Her hypervisibility became one way of unseeing her, the blinding lights of constant exposure meant that people often missed her more gracious, loving, affable, caring, selfless side. More homeless kids were taken in by Fassie, friends assisted by her and distant people aided by her generosity than any headline ever cared to mention. For someone who was known to have a loose mouth, ever talkative and never shy about most things, a bragger whenever she could – so much of her generosity took place behind the watchful eye of the media. In an interview with Lara Allen, Fassie said it better than anyone else could “you can’t write me down. It will be just like the rubbish all those other motherfuckers write. If people want to know about me, if they want to know about me, if they want the real me, they can listen to my music. Tell them to buy my CDs. Bongani (her son) needs the money.”

In the storm of her addiction to crack cocaine and other substances, when most people had lost the hope of ever being mesmerised by the stage presence of that nineteen year old who stole the hearts of Black South Africans in 1983 with her hit “Weekend Special” – Fassie emerged from the ashes of intoxication, barely herself, but enough spark for long-time collaborator Thwala to produce a seminal album titled Memeza in 1998. It came with a song titled “Vulindlela” which became the song that signalled the end of the decade and ushered in a new one. This song became the anthem of a much needed transition in South Africa, it spoke about the joy and pride of finally seeing a son get married and bring dignity to the family name. The cheek in this song often feels quite metaphorical – as if she was releasing pent up energy against all those people who had lost hope in her and were now forced to stand in the rainbow of her new success and reinvention. It’s a probable reading when one thinks of how much approval and affirmation Fassie needed but it is also complicated by her super individualist attitude and anti-group mentality sensibilities that led Brenda Fassie to do whatever she wanted and always get her way.

Ultimately, after failed rehabilitation attempts, she entered the prison of addiction and never made it out alive succumbing to death in 2004 at the tender age of 39 after going into a coma and suffering brain damage caused by an overdose of crack cocaine. Fassie was addicted to attention, drugs, and alcohol, it was often said that she woke up and went to sleep with a drink in hand. She suffered much tragedy including the drug overdose and death of her lesbian lover Poppy Sihlahla but Fassie is not the sum total of low or her many high moments – she must be understood as both those things and we must always leave room for the fact that so much of her strangeness is a mystery to us and our best compass for her truth lies in her music. Fassie’s catalog is a beautiful mine field that reflects the many faces and moments of South African history.